Talent is overrated. The name of the game is practice.

The craft of the top performer isn’t perfect because of their talent. It’s perfected by the endless hours of practice they put in. And so can you.

Top performers inspire awe. Whether it’s top athletes, artists, public speakers. The Mozarts, the Tiger Woods or the Sharapova’s of the world are so good that the gap between us mere mortals is ridiculously large. It’s unfathomable how they’ve ever gotten this good. The only explanation that makes sense is that they must’ve been born with an enormous amount of talent.

We believe it because when we tried to play the piano, golf or tennis, it sucked. It sounded like a mess, we missed the ball or we hit the net. We quickly saw “this is not for us”.

The more you know the less it is about talent

However, the more you know about the top performers, the less it becomes about talent.

Wolfgang Mozart's father was a domineering father, a composer in his own right and a pedagogue. He was hell-bent on teaching young Wolfgang to be a great composer and checked all his work before anyone else saw it.

Tiger Woods' father, again, was a golfer and a teacher. He and his wife made it their number one priority to teach Tiger golf. What for other kids were cartoons, for Tiger was watching his father swing his gold-club. By age 19, he had been practicing for 17 years! And what's funny, both Tiger and his father don't suggest he came into the world with a particular gift.

Maria Sharapova grew up watching her dad play tennis. She started playing at the age of 4. But what set her apart was her tenacity to keep improving. The patience and discipline that were needed for that were instilled by her mother - another teacher - who made her memorize Pushkin novels for an hour every evening. That discipline to sit with the uncomfortableness is something Tim Ferriss sees with a lot of high-performers he interviews.

When you look at the best violinists and compare them to simply good violinists, you'll see that they've literally practiced twice as many hours by the time they become 18 (7.400 hours vs 3.400) and keep up their rigorous practice schedule at that rate.

And take endurance runners. They have larger than average hearts, an attribute that most of us see as one of the natural advantages with which they were blessed. But no, research has shown that their hearts grow after years of intensive training; when they stop training, their hearts revert toward normal size.

The examples are aplenty. IQ-tests can be practiced. Memory can be trained. Skill acquisition can be hacked. The more you learn about it, the more you find out about the importance of everything besides talent.

What was the difference?

We see that talent can never be the full story. Even being born with all the talent in the world doesn't guarantee becoming good at it.

So - besides the possible gap in talent - from examining the top performers we can see that the main differentiators between them and us are cultivation, that they got over the hump and practice.

Cultivation

Firstly, they found themselves in a situation that allowed them to cultivate their talent. So much needs to go right for someone to land on the trajectory that allows you to become the best of the best.

Being born in the right month of the year (so you're older than the rest of your cohort of the talent-teams), family background (area of expertise of parents, financial situation and willingness), and serendipitous moments.

Up to the moment you can control it yourself, you need the luck to have those chances.

Over the hump

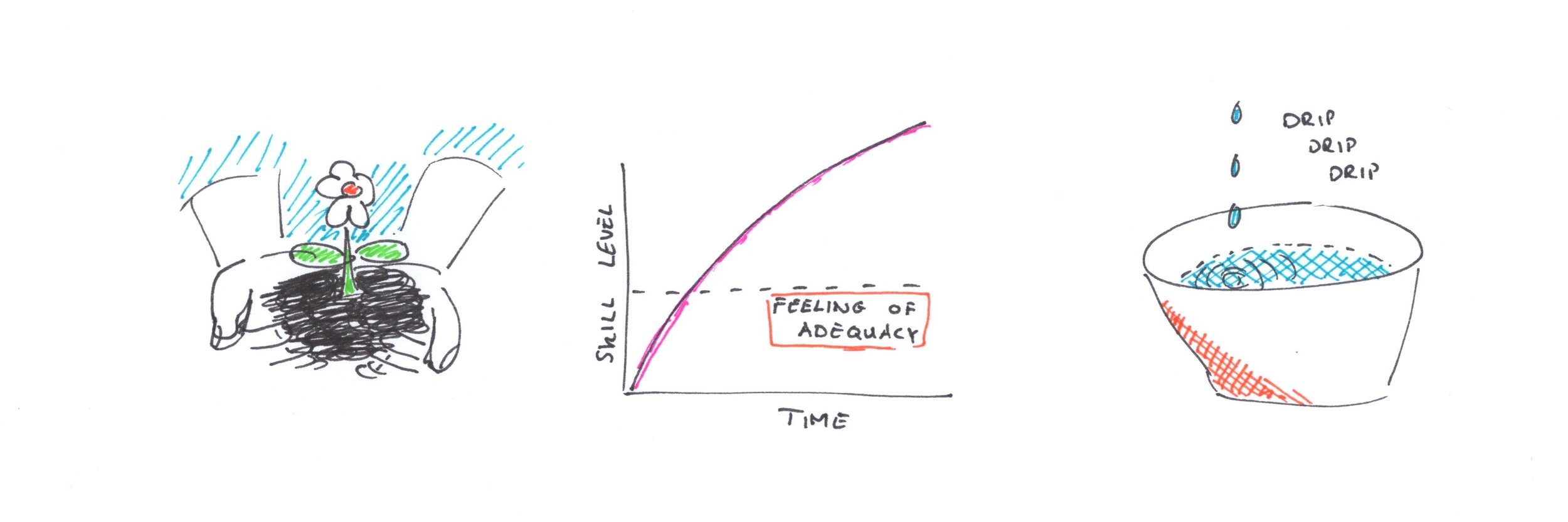

Secondly, when they started playing/practicing, they stuck with it while most people would've concluded that it wasn't for them.

Because they enjoyed it. Because they - as a kid - didn't have much of a choice but to continue. Because when they started, they had already cultivated the patience to stick with it during the initial period of being bad. Because they had good teachers to make smooth out the process.

After they got over the hump, they got to a level at which they could enjoy it even more. This kept them motivated to practice more and start becoming better than their peers after which talent scouts show up.

Practice, practice, practice

But the most important difference maker: They've practiced an insane amount of hours to improve their skills. They understood that talent remains latent if it isn't fostered, honed, exercised and refined.

They knew it wasn't fun, but it was needed to become great. They fell in love with the process and not just the results. So they sacrificed all their time to practice.

Why chalk it up to talent?

These differences don't answer whether or not all the right circumstances and practicing can make up for a talent gap. Maybe to become the very best, you need both insane amounts of talent and insane amounts of practice.

But they do explain a lot of the differences in the results. So much so, that it makes me doubt whether or not talent is needed at all for slightly more modest goals.

So why do we keep ascribing so much of the differences between the very best and us to talent?

Mystique

Part of it is that the mystique is part of the fun. You're imagining gods at work. The view of a grind and hours upon hours of practice sounds incredibly unsexy.

Selective

Funnily enough, it's always the same types of skills that we ascribe to talent. It's sports, arts (most notably music), and aptitude for science or languages. Sometimes for people skills (communication, emotional labor, leadership).

But when we see someone with well-developed abs, we don't say that she was musclebound as a baby. For some skills and attributes, we accept that a lot of work goes into developing them.

Talented in what exactly?

And in what exactly were these top-performers talented? It makes no evolutionary sense to have a specific "violin gene". You can just see those early Homo Sapiens in East Africa fiddling off predators, can't you?

Any skill, be it playing the soccer, playing the violin, or physics - can be deconstructed into many different sub-skills. Sub-skills for soccer like sprinting, dribbling, kicking, game tactics, etc.

On the one hand, the more you break down a skill, the more overwhelming the list becomes. But on the other hand, the simpler all the individual sub-skills are to focus your practice on to develop them.

Break it down these sub-skills even further, and you come to foundational sub-skills like walking technique, balance, dexterity, endurance, emotional control, etc.

You can imagine that a kid could - under the right circumstances and interactions - develop these foundational skills unconsciously.

The stronger the foundation, the easier it becomes to pick up a new sport or other skill. The speed at which someone picks up a sport can then either be attributed to talent or to a developed base of foundational skills.

So, maybe these child-prodigies had a lot of "practice" on their foundation before they started training.

Get out of jail free card

To ascribe something to talent is also the perfect argumentative "get out of jail free card". How can she possibly do that? Talent! How does he learn so fast? Talent! It explains everything! It can't possibly be learned. The amount of practice that would be needed for that is immense. That's even more unfathomable. Talent!

So, instead of researching further, talent is the easy way to explain it.

Off the hook

But, it's not just a "get out of jail free card" for the argument. It also let's you off the hook. If you didn't make it at something that required talent, you can simply explain it away that it wasn't meant to be/the deck was stacked against you/you didn't stand a chance.

It would be much more uncomfortable to stomach that you simply didn't work hard enough or weren't willing to make the necessary sacrifices. That it was within your control and you were responsible. That it doesn't let you off the hook when something doesn't come easily to you.

You can see why it's tempting to believe in the need for talent. Because if you question it, there's nothing you could find out that doesn't also come with responsibility for yourself.

So, we keep calling athletes gifted or talent. But even if that's true, it's definitively doing them a disservice. Because it under-appreciates all the work and sacrifices that went in.

A better story around talent

I don't have an answer for you whether talent is needed.

Maybe we need to have talent to become good at something. Maybe more than we possess.

But we definitely over-appreciate its importance simply because it's easier. And we could benefit from a better story around it.

Everyday skills

In our belief in the importance of talent, we often use these top-performers as references. But the skills that they possess are of little use in our everyday lives.

In our life or work, we rarely need to swing a little ball in a hole a kilometer away. And the skills we do need, are skills that can be learned. Like understanding science, planning, being organized, making good decisions or doing the scary thing. These can be developed.

If we stop believing in the need for talent for these skills we stand a chance in developing them and improving our lives.

How good is needed?

The amount of practice being equal, the most talented player wins. That's why, to become the very best in the world, you might need talent. But most of us don't need to become the very best, we just need to become good enough at a skill to apply it.

Lots of practice can overcome any lack of talent if the goal is to become 'merely' good.

The 10.000-hour rule you might now, states that to become world class at a skill, it requires 10.000 hours of dedicated practice. However, to become adequate or reasonably good at a skill, sometimes only 20-40 hours is enough.

That puts a lot more skills within arm's reach when we are willing to put in the practice.

Control

By believing in the need for talent, you put a lot out of your zone of control. By focusing on the things out of your control, you lower your chances. No matter how much talent is needed, we use it as an excuse too easily.

So, stop worrying about that you might not have enough talent. Or, that you've started too late. Or, that you haven't gotten the cultivation when little. All this is useless. Even if it all would have been helpful to have then, you can't change it now.

What you can control is to make a conscious decision to improve through high repetition and deliberate practice. These are the most important difference makers within your control to increase your performance level.

3 Mindsets for Practice

Let's look at 3 mindsets that can help you when practicing a skill.

Expect it not to go right, right away If you could instantly become good at it by a wave of a magic want, everyone would do it. There are good practices, but the first time you try it, you'll probably fail. But this is good, because the second time you'll do better.

Appreciate the uncomfortableness of inadequacy Becoming good at something you are currently bad at requires practice. And practice isn't fun. It's continuously putting you in a situation where you are not good enough at it yet. It's feeling inadequate continuously.

Becoming at ease with the feeling of not being able to do it. That's what Sharapova had. It becomes about the process, not the outcome.

Expect it to require lots of reps It will take time. So when after a while you'll still not be really good, you won't freak out. You'll continuously try to improve the practice regimen, but you know that it takes time.

You'll build up practice-stamina.

Actually, that's why you do it. Because the demands of achieving exceptional performance are so great over so many years, no one has a prayer of meeting them without utter commitment. It's scarce because nearly no-one else wants to make it through the dip. And that's why you do it. It's the pain that you choose.

What now?

Concluding, talent might be important, but it's not nearly as important as we think it is.

For most skills and goals, it's entirely possible for you to become good at it. Whether or not you're willing to do the work is the real question.

It's up to you to make the decision. So examine what personality traits you've got and what skills you already possess.

Decide what you want to become better at (and which skills are fine as is at this moment) and commit to practicing it, knowing full well that this will not always be fun.

Do some research. Deconstruct that skill to see what sub-skills it consists of. Select the most ones that give the biggest bang for your buck. Sequence your practice in the right order to quickly get to a level that you can enjoy. (this is Tim Ferriss' DSSS-framework)

While developing this skill, you'll be learning the meta-skill of cultivating your skills and developing the stamina to practice.

Inspiration for this article:

Geoff Colvin - Talent is Overrated; What really separates world-class performers from everybody else

The Tim Ferriss Show with Maria Sharapova

Thanks for reading!

I hope this helps you. If so, sharing the article really helps others find it too. Both would be much appreciated!

Subscribe to me on Medium if you want to follow what I write.

Want more?

Want to really get to work on this with me? Want more focus and clarity in your life and work? Want to adopt the right mindset in approaching developing your purpose?

Join me in Utrecht for my as-good-as-free Masterclass "Aligning with Purpose; The Curious Way" on Friday, November 10th. More info and sign up here!